On a trip to P’atzcuaro, Mexico in June of 2009, I was introduced to Derli Romero, who runs the Center for the Production of Graphic Arts at the Collegio De Jesuita — a public printmaking workshop where invited artists from around the world come to produce etchings, lithographs, woodcuts and mixed-media prints. I produced a small drypoint etching on copper entitled “Passenger.” I loved the shop and the printers who work there and decided to propose a major project, which would enable me to drive to P’atzcuaro and spend a month working there.

Upon returning to Tennessee after the first trip, I worked up a proposal and emailed it to Derli. It was a two-tier proposal. I proposed a smaller scale project where I would fly down, stay for two weeks, and produce a series of drypoint etchings on copper, which the printers would edition. Or, my preference would be to produce a large-scale, multi-block, color woodcut working for a month with the printers to produce the edition. Derli emailed back and said, “I like the ideas, let’s do it all.” I then applied for and received a “Professional Development Grant” from the Tennessee Arts Commission, to whom I am grateful for helping make this project happen.

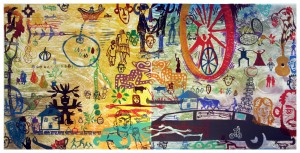

That occurred in the fall of 2009 and the timeline for producing the prints would be May–June of 2010. I knew that they have a very large etching press so the size of the image would be 30×60 inches. I began thinking about the image and began to do preliminary drawings and watercolors. Having worked as a printer at Experimental Workshop in San Francisco for three years in the eighties, on complex woodcut projects such as this, I knew what I was getting myself into in terms of technical difficulty and effort. I also knew that after doing the drawings and watercolors, separating and transferring the image to the blocks, and cutting the blocks, which would take months, and then spending a month printing the edition, I better make sure I was convinced about the aesthetics and content of the image. So, I finally came up with a watercolor, to scale (30 × 60 inches), that I thought would stand up under the scrutiny it would receive.

The theme would be “the border” and the 30 × 60 image would be divided in half, the middle symbolizing the border. The right side would be the American side and the left the Mexican side. I wanted to talk about what we all have in common and how the border is an invisible division separating two different cultures, each with it’s own beauty, tragedy, history, and politics. With the current debate on immigration raging in the U.S. the print represents even more than my original intent. What we have in common is symbolized by the fruits and seeds and that we all need to eat; parents, children, and the importance of family; that we all need housing; that we all work, symbolized by the shovel; that we all need to have fun, symbolized by the skateboarder; and that we are all passing through time together, symbolized by the wheel.

The two figures at the top shaking hands across the border are Abraham Lincoln and Benito Juarez, who was the first full-blooded indigenous president of Mexico, governing at the same time as Lincoln and facing similar challenges. The two knew and admired each other. This image of the two shaking hands on a pedestal is modeled after a concrete sculpture by Tennessee folk artist E.T. Wickham. On the American side there is a large American car crossing the border, symbolizing the increasing worldwide concern about energy use; a baseball; an American eagle; a guitar with flowers growing out of it, symbolizing the lively role music plays in both cultures; the Statue of Liberty; a pair of male and female figures taken from a Navajo textile design; mules pulling a plow, symbolizing food production; and figures walking, rowing, riding, and flying towards the border.

On the Mexican side there is an image of a stone carving of a couple in a boat (I saw this sculpture in a stoneyard in the town of Tzintzuntzan, not far from P’atzcuaro); a dark brown version of a Mayan paper cutout of a seed god; a ruby-throated hummingbird, which itself crosses the invisible border every year to migrate from Mexico to our back yards; a line image of an Aztec holding a cup of pulque; a family walking towards the border; a stretched out horse crossing the border; a woman with outstretched arms welcoming people; and a jaguar (a symbol of power in both Maya and Aztec cultures) reaching across the border towards it’s American counterpart (jaguars also once roamed the American south and southwest).

I arrived in P’atzcuaro in mid-May, after a four-day drive with a truck full of inks and other supplies for the shop, as well as three already-cut woodblocks and the paper for the large print. My first task was to mix inks. Using the watercolor as a guide, I mixed the 33 colors in three days. By rolling different colors onto specific areas of the same block, a number of different colors could be printed during the first pass through the press. With three printers and myself we then began “proofing,” the process of homing in on the perfect print, called the bon a tirer (French for good to print). It took us two days to create this model print, which I would sign and designate “BAT” so it could serve as a prototype for subsequent prints. However, I didn’t want the printing process to be too factory-like or mechanical, so I was open to collaboration with the printers as to how to improve on the print as we went-to adapt colors so that all of the prints were not exactly alike — in hopes that it would be fun for everyone. With four printers we could print two or three large prints a day. The edition ended up being 17 with each printer getting a print; the Center getting two copies; and me the rest. In the third week we printed fragments of the print in different colors and also did “ghost” images on rice paper, in which I would put small sheets of rice paper over the large blocks after they had been printed to pick up the residual ink left on the blocks. I had also brought four already-drawn copper drypoint plates, which the printers editioned on a special paper we ordered from Mexico City.

The whole experience was life-changing-eye-opening and invigorating for my studio work here in Tennessee. I will be returning yearly to P’atzcuaro. With an open invitation to work at the Center, I look forward to creating more work there influenced by Mexican history and culture.